Seriously Simple Snippets One Page at a Time

Home >

Keep up to date with Seriously Simple Snippets.

Keep up to date with Seriously Simple Snippets.

essentialism

essentialism

The Disciplined Pursuit of Less

Greg McKeown

The Book in Two Sentences

- “Essentialism is a disciplined, systematic approach for determining where our highest point of contribution lies, then making execution of those things almost effortless”.

- “The way of the Essentialist rejects the idea that we can fit it all in”.

The Big Ideas

- “Only once you give yourself permission to stop trying to do it all, to stop saying yes to everyone, can you make your highest contribution towards the things that really matter”.

- “Essentialists invest the time they have saved into creating a system for removing obstacles and making execution as easy as possible”.

- “Essentialism is not a way to do one more thing; it is a different way of doing everything. It is a way of thinking”.

- “To embrace the essence of Essentialism requires we replace false assumptions with three core truths: ‘I choose to’, ‘Only a few things really matter’, and ‘I can do anything but not everything’.”

- “Essentialism distinguishes the vital few from the trivial many”.

Essentialism Summary

- In his book How the Mighty Fall, Jim Collins explores how “the undisciplined pursuit of more” was a key reason for failure.

- “The way of the Essentialist rejects the idea that we can fit it all in. Instead it requires us to grapple with real trade-offs and make tough decisions. In many cases we can learn to make one-time decisions that make a thousand future decisions so we don’t exhaust ourselves asking the same questions again and again”.

- “The overwhelming reality is: we live in a world where almost everything is worthless and a very few things are exceptionally valuable. As John Maxwell has written, “You cannot overestimate the unimportance of practically everything.’”

- Question: “Will this activity or effort make the highest possible contribution towards my goal?”

- “Studies have found that we tend to value things we already own more highly than they are worth and thus that we find them more difficult to get rid of.”

- Question: “If I didn’t already own this, how much would I spend to buy it?”

- “Half of the troubles of this life can be traced to saying yes too quickly and not saying no soon enough” Josh Billings

The three realities of the Essentialist:

- Individual choice: We can choose how to spend our energy and time.

- The prevalence of noise: Almost everything is noise, and a very few things are exceptionally valuable.

- The reality of trade-offs: We can’t have it all or do it all.

We can ask three questions:

- “What do I feel deeply inspired by?”

- “What am I particularly talented at?”

- “What meets a significant need in the world?”

- “LinkedIn CEO Jeff Weiner sees ‘fewer things done better’ as the most powerful mechanism for leadership”

- “There are three deeply entrenched assumptions we must conquer to live the way of the Essentialist: ‘I have to’, ‘It’s all important’, and ‘I can do both’. Like mythological sirens, these assumptions are as dangerous as they are seductive. They draw us in and drown us in shallow waters”.

- “To embrace the essence of Essentialism requires we replace false assumptions with three core truths: ‘I choose to’, ‘Only a few things really matter’, and ‘I can do anything but not everything’.

- “These simple truths awaken us from our non-essential stupor. They free us to pursue what really matters. They enable us to live at our highest level of contribution”.

- Question: “If you could do only one thing with your life right now, what would you do?”

- “To become an Essentialist requires a heightened awareness of our ability to choose”.

- “When we forget our ability to choose, we learn to be helpless. Drip by drip we allow our power to be taken away until we end up becoming a function of other people’s choices – or even a function of our own past choices”.

- “Instead of asking, ‘What do I have to give up?’ [Essentialists] ask, ‘What do I want to go big on?’”

- “In your life, the killer question when deciding what activities to eliminate is: ‘If I didn’t have this opportunity, what would I be willing to do to acquire it?'”

- “And while conforming to what people in a group expect of us – what psychologists call normative conformity – is no longer a matter of life and death, the desire is still deeply ingrained in us”.

- “Essentialists accept the reality that we can never fully anticipate or prepare for every scenario or eventuality; the future is simply too unpredictable. Instead, they build in buffers to reduce the friction caused by the unexpected”.

- “When faced with so many tasks and obligations that you can’t figure out which to tackle first, stop. Take a deep breath. Get present in the moment and ask yourself what is most important this very second – not what’s most important tomorrow or even an hour from now”.

OPPM™ and essentialismOPPMs communicate project plans, then their performance, deliberately distinguishing the vital few from the distracting many; so essential things are clear and concise. OPPMTM is a disciplined systematic communication process, which provides:

|

Download PDF

Download PDF

The Presidential Transition Act made it the law, the OPPM made it simple

The importance of effective and well-planned presidential transitions has long been understood. The Presidential Transition Act of 1963 provided a formal recognition of this principle by providing the President-elect funding and other resources “To promote the orderly transfer of the executive power in connection with the expiration of the term of office of a President and the Inauguration of a new President.” The Act received minor amendments in the following decades, but until 2010 all support provided was entirely post-election. The Pre-Election Presidential Act of 2010 changed this by providing pre-election support to nominees of both parties. Its passing reinforced the belief that early transition planning is prudent, not presumptuous.

The Romney Readiness Project was the first transition effort to operate with this enhanced pre-election focus. While Obama’s re-election prevented a Romney transition from occurring, it is hoped that the content of The Romney Readiness Project book can provide valuable insight to future transition teams of both parties.

The OPPM was used as the overall project management system for the Project. For each phase a master OPPM (described as “Level 1”) was created to show all the major deliverables, schedule, supporting activities, and who was responsible for each. This OPPM was then cascaded down to subsidiary OPPMs covering each activity in more detail. Generally speaking, one line item on the Level 1 OPPM was expanded to an entire Level 2 OPPM, with a similar expansion of detail between Level 2 and Level 3. Examples of Level 1, 2, and 3 OPPMs for the Readiness Phase are shown in Appendix 3.1 of the book.

Clark Campbell, Founder & Author

Download PDF

Download PDF

Agile Joins the OPPM Family

The fourth book in the OPPM Series is scheduled for release by John Wiley & Sons on Christmas Day. B&N and Amazon are now accepting advance orders. In addition to vivid color, and continuous OPPM improvements, this book will introduce the Agile OPPM. Therefore, a few comments comparing traditional with agile project management will be helpful. And of course, we need a visual.

The above figure shows the basic similarities between traditional and agile project components.

- Each makes progress over time toward a vision.

- Each requires cost and resources.

- Each strives for higher quality and lower risk.

This second visual reveals that the processes and the approach differentiate these two powerful project methodologies. Suppose the traditional triangle on the left represents a project to build a Boeing 737 aircraft. The 737 entered airline service in 1968 and is the best-selling jet airliner in the history of aviation, with more than 7,000 aircraft delivered and more than 2,000 on order as of April 2012. The vision is clear, we know exactly what we want, and the plan for delivering the value includes the whole vision. Engineering specifications are clear, supply chains are well defined, production costs are precisely known, and manufacturing times are defined and documented. Quality is built in to the process with operational excellence, and the acceptable parameters for risk reducing tests are standardized.

We know what we want, how long it takes, how much it will cost, and how to guarantee high quality with the lowest risk. And, we release a completely finished aircraft, capable and ready to fly.

Now let’s suppose that the triangle on the right of Figure 3.3 represents the agile approach to designing and deploying a new in-dash GPS system for New York’s fleet of taxicabs. We have a fixed budget and a highly publicized date, 24 weeks away, when the mayor plans to announce the new upgrade.

We have the high-level outline of a vision, yet there is disagreement among various stakeholders on which features are most important. We have selected 20 cabs into which we will place the latest release of our GPS every six weeks. We will plan and deliver it in three 2-week sprints prior to each of four releases. Each release will provide fully working software for a minimally marketable set of features. We will set and reset feature backlogs and priorities along the way by working with cab drivers, customers, and other stakeholders.

As we progress through each sprint and release, we will be adjusting our vision as priorities are repositioned, technology is refined, and learning is acquired by our development team. When the mayor presents the newly equipped taxis to the city in six months, he declares the project on time and on budget, with a final vision a little different than was originally presumed, acknowledging that quality was addressed and improved in each iteration. He is aware of the reduced risks of missing the delivery date of his announcement or exceeding the budget, while continually surpassing stakeholders’ expectations, even though those expectations are quite different at project completion than they were in the beginning.

Agile OPPM templates and examples will be made available for download in conjunction with the release of the book.

Clark Campbell, Founder & Author

Download PDF

Download PDF

If it has a staple through it, or a paperclip around it - they won't read it

Many years ago, I was teaching an executive MBA course in project management. Every other weekend, the class would meet and two of the students had to prepare (to the best of their ability) an executive-level status report on an existing project. In the first class meeting, two of the students volunteered to “get the pain out of the way” and be first to team up and prepare a status report for the next class meeting.

In the next class meeting, they handed out a 15-page status report to each student. I then followed them around the classroom, picked up all of the status reports, and disposed of them in the trash can while the whole class watched. The two students that prepared the reports were quite upset. I then told them to prepare another report for the next class meeting and, if the report had in it a staple or paper clip, I would dispose of it in the same way.

The moral to the story is clear: Executives do not have time to read what’s on their desk already, so why give them too much information in which case they will either refuse to read it or study it with a microscope and find a fault. Executives want the answers to two questions: Where are we today? And where will we end up? Do you really believe this cannot be accomplished on a single sheet of paper? The One-Page Project Manager series of books are encouraging you to do just that. Making this part of your Project Management Methodology will simplify and improve your project communication, especially with busy executives.

—Harold D. Kerzner, PhD

Senior Executive Director International Institute for Learning, Inc.

Clark Campbell, Founder & Author

Download PDF

Download PDF

OPPM and the PMBOK

More than 400,000 professional project managers know that PMBOK is the acronym for A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. The PMBOK originated as a white paper in 1987, with a first edition book published in 1996, second edition in 2000, third in 2004 and the fourth December 2008. A fifth edition is scheduled for publication in 2013. The Project Management Institute (PMI) describes the PMBOK as the “recognized standard for the project management profession.” PMI further states that it “provides guidelines for managing individual projects. It defines project management and related concepts and describes the project management life cycle and the related processes.”

That being said, still many practicing project managers, and readers of the OPPM books, are not familiar with the PMBOK.

With this Snippet, we desire to provide readers of all experience levels a “seriously simple” visual display of the PMBOK. We will also drill down on Communication Management showing how the OPPM comfortably aligns with PMBOK processes and knowledge areas while accelerating communication effectiveness.

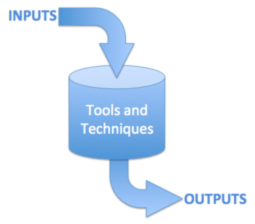

A comprehensive interrelated framework supported by the concept of “processes” undergirds PMI’s view of projects and project management. Processes are a cluster of interconnected activities performed to deliver a planned result. The planned results are the outputs that a process generates by applying various tools and techniques to a collection of inputs. This inputs; tools & techniques; outputs process model is PMBOK’s fundamental building block.

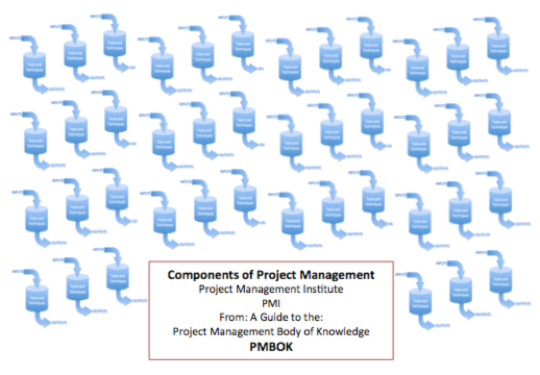

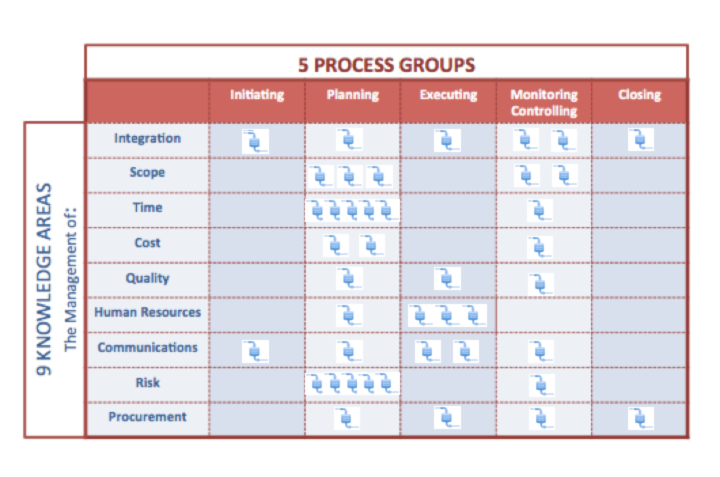

The Guide recognizes 42 different processes (see below) which overlap and interact throughout the phases of a project. Outputs from previous processes become inputs to others, whose outputs then provide inputs to successive groups of processes. Project managers, in collaboration with their project team, must determine which processes are applicable to their specific project.

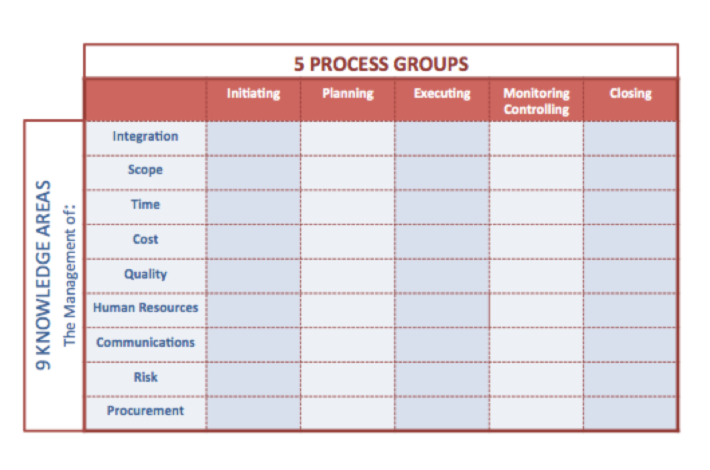

The PMBOK’s 467 pages are largely focused on describing and navigating this maze of interconnectivity. In a brilliant stroke of simplification, they have aligned each process with one-and-only-one of 5 Process Groups, and one-and-only-one of 9 Knowledge Areas thus providing the capability for a 5 by 9 display.

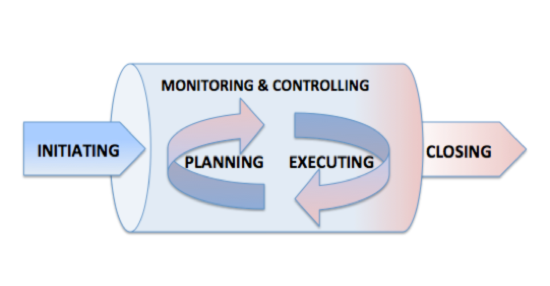

The 5 Process Groups are:

- Initiating – defining and securing authorization to begin.

- Planning – establishing scope and defining the actions required to attain it.

- Executing – performing the work to deliver the plan

- Monitoring and Controlling – tracking progress and handling changes.

- Closing – finalizing activities and formally closing the project.

A visual display of the Process Groups helps to see how projects begin with the Initiating group and end with the Closing group. Panning and Execution follow Initiation and are iterative during the project while Monitoring and Controlling operate throughout the project.

The 9 Knowledge Areas are about management. Here, processes are grouped in alignment with the various executing and administrating skills necessary for successfully running a project.

By placing each of the 42 processes into their respective Process Group, and Knowledge Area, we have a seriously simple context or framework enabling us to visualize, from the 30,000-foot level, the full construct of project management.

OPPMs can be an important part of most of the 42 project processes. Communications Management however, is the Knowledge Area where the OPPM can amplify project management performance most directly. As seen above, Communications Management includes five specific processes resident in 4 of the 5 Process Groups.

OPPMs and Communication Processes

1. Identify Stakeholder Process: Referencing the project charter and enterprise environmental factors, the project team conducts a stakeholder analysis to identify key stakeholders and then develop a stakeholder management strategy.

OPPM Application – The OPPM documents and communicates the project plan in sufficient, yet efficient detail. Stakeholders that have a clear picture of the project are better prepared to support project efforts. Thinking through the various OPPM building and reporting steps helps identify diverse stakeholder interests.

2. Plan Communications Process: With stakeholders identified, and a stakeholder management strategy plan in hand, the team analyses communication requirements. They utilize communication technology, communication models, and communication methods to prepare a communication management plan.

OPPM Application – The OPPM is constructed to reflect stakeholder requirements. The communication cadence is determined and built into the OPPM. Who updates and releases the OPPM and to whom it will be distributed is determined. It is important for OPPM readers to understand the meaning of open and filled circles and boxes along with the implication of the stoplight colors.

3. Manage Stakeholder Expectations Process: Knowing who they are and what is important to them, the project manager applies effective communication methods together with interpersonal and managerial skills to manage stakeholder expectations. Various plan updates may result.

OPPM Application – OPPMs are easily read, and easily changed. Expectations are clear and concise. Concerns are often addressed before becoming issues. The OPPM displays the what, who, how long and how much, and then addresses the why and what’s next. Frankly, stakeholders like OPPMs; they know more of what they want to know, when they want to know it – on one page.

4. Report Performance Process: With work performance and forecast inputs on scope, schedule and costs, together with quality and risks, the team prepares the project status report.

OPPM Application – The OPPM is the performance report. It shows plan versus actual for costs, tasks, schedule, and risk. Preparation is not difficult or time consuming and stakeholders will read it.

5. Distribute Information Process – Quoting the PMBOK “Performance reports are used to distribute project performance and status information, and should be as precise and current as possible.”

OPPM Application – OPPMs are quickly prepared, therefore current. OPPMs are precise and candid. OPPMs are easily distributed in print and digital formats and may be clearly referenced in web and video conferences.

One final thought. The dimensions of project communication activities are listed in the PMBOK and are shown below. As you read through them, now that you have finished this book, think how OPPMs provide a seriously simple solution within each.

- Internal (within the project) and external (customer, other projects the media, the public)

- Formal (reports, memos, briefings) and informal (emails, ad-hoc discussions)

- Vertical (up and down the organization) and horizontal (with peers)

- Official (newsletters, annual report) and unofficial (off the record communications)

- Written and oral, and

- Verbal and non-verbal (voice inflections, body language)

Clark Campbell, Founder & Author

Download PDF

Download PDF

Forward, The NEW One-Page Project Manager

You have in your hands a book that is both a critical tool for, and a symbol of, our innovation economy.

Our 21st Century workplace is the scene of rapid, visible evolution. This rapid evolution means we are surrounded by projects. Some projects are huge, such as a new commercial airplane model. But the proliferation of projects is due more to an increase in small projects, such as implementing standardized processes in an operating room, a promotion campaign for a winery, or opening a new office for a growing business. There are many reasons the pace of change and the number of projects are increasing, but there is no doubt it is true, for the evidence is all around us.

Projects generate chaos. How could they not? The definition of a project is work that has a beginning and end, and produces a unique product or service. By their nature, every project has an element of discovery, doing something that hasn’t been done exactly that way before. Every project is different than the last one. It’s the opposite of the 20th Century focus on continuous process improvement – refining the way we manufacture a car or process a bank loan until we drive out all inefficiency and error. Managing a single project may not quite constitute chaos, but as projects proliferate we find ourselves juggling a collection of increasingly diverse tasks, goals, and resources.

The project-driven workplace emerged in the 1990’s. In that one decade, the discipline of project management broke out of its construction- and defense-industry niche and spread throughout all organizations – for profit, non-profit, and government. With it came an explosion of training, methodology, software and certification; all directed toward gaining control over the ever-increasing complexity associated with managing more and more projects.

Our approach to manage the complexity of projects has become equally complex. Project Management Offices (PMO’s) are staffed with expert project managers. Enterprise project management software attempts to systematize the juggling game; corralling our jumble of projects into a common framework and database. All of this effort and structure introduced to get our arms around this chaotic work has allowed us to juggle more and bigger projects.

Yet there have been two significant departures from this trend toward larger, more complex project management. The first, the Agile software development approach, broke the paradigm of rigidity and control because it became clear that increased structure both slowed projects down and degraded the quality and usefulness of the resulting software. Within a decade, the appeal of Agile transcended the software and information technology industries and is being used with other kinds of projects where discovery and rapid learning play major roles in project success. Agile does acknowledge the complexity of projects, but it addresses the complexity with principles and techniques that are designed to coexist with complexity rather than conquer it.

The second significant trend away from complex project management is described in this book, the One Page Project Manager, or OPPM. The OPPM also accepts that projects can be large and complex, but insists that to effectively manage them we must be able to distill the complexity to bring the major themes into focus. Using the OPPM we can simultaneously pay attention to several key dimensions of project performance, producing a sufficiently complete understanding to make good decisions.

How is it possible that we can manage a major project using the information formatted onto a single page? Even simple project management methodologies call for a half dozen separate documents. But that is the magic and the value of the OPPM. Project management is already a discipline populated by graphic techniques, because a picture is not only worth a thousand words, it may be the only way to truly synthesize and digest the meaning of those words. The OPPM takes synthesis and summary to a new level.

During twenty-plus years of teaching and consulting in the field of project management, my team at The Versatile Company has worked with many thousands of projects and project managers in industries as diverse as health care, education, aerospace, and government. Throughout this time I have prized the practical over the theoretical. I particularly attempt to focus on the minimum management overhead that produces the greatest productivity benefit, so it is natural for me to appreciate the OPPM. I am also naturally skeptical, so I was cautious embracing it. I’ve developed my own rules of thumb for evaluating a project and the minimums needed for effective management, and they are published as the Five Project Success Factors in my own popular book, The Fast Forward MBA in Project Management. I used the lens of the five factors to view the OPPM and was impressed that it contributed to every one of them.

- Agreement among the project team, customers, and management on the goals of the project. The OPPM clearly and concisely states the project’s goal at the top of the page, with sub-objectives listed on the left column. Together, these provide clarity to key stakeholders about the purpose and scope of the project.

- A plan that shows an overall path and clear responsibilities and that can be used to measure progress during the project. This may be the OPPM’s greatest strength – synthesizing and summarizing the details of the project plan and task status to provide a useful high-level understanding of the plan and our progress.

- A controlled scope. Uncontrolled scope is the number one threat to on-time, on-budget performance. Uncontrolled scope means we allow additional tasks and objectives to be added to a project without consciously and formally accepting the related cost and schedule increases. Using the OPPM, it is clear what our major tasks are, when we will meet major schedule milestones, and how much we plan to spend. Changes that attempt to creep into the project will become visible in one or more of these dimensions quickly, providing notification to the project manager and the project’s owners that they need to contain the change.

- Management support. Every project needs support from management. Project managers and teams don’t have sufficient authority to accomplish the project on their own. The age-old problem is getting busy executives to engage based upon accurate project information. This was the genesis of the OPPM: creating a single project dashboard that enables meaningful, informed involvement from managers with multiple projects under their span of control.

- Constant, effective communication among everyone involved in the project. This is the essence of the OPPM.

Amazingly, the OPPM is the product of a very few executives and one in particular, Clark Campbell. Among all the other methods and techniques in the world of project management, it is nearly impossible to find one with a single inventor as most techniques evolved out of common usage across hundreds or thousands of projects. The clear exception is Henry Gantt, who introduced the now ubiquitous chart that bears his name literally a century ago. Like Gantt, Clark Campbell and his colleagues produced this new graphic for project reporting out of necessity and honed its design through use.

This new edition benefits from five years of feedback since its initial publication in 2007. Appropriately, it also includes a modified OPPM for Agile.

In our innovation economy characterized by rapid evolution and abundant projects, project management has taken on increased importance. It is also important to realize that we need both complex and simple approaches to managing projects. The OPPM does not replace the complex methods – Clark Campbell is clear about that. The OPPM creates an interface between the sophisticated, specialized skills of professional project managers and the many other project stakeholders whose expertise is needed for the project.

I congratulate Clark on his success pioneering this timely management and communication tool. It is well suited to the demands of leadership in these turbulent times.

Eric Verzuh, PMP

President, The Versatile Company,

www.VersatileCompany.com

Author, The Fast Forward MBA in Project Management, 4th ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2012